Was perusing the Stack this morning when I came across this article about Aristophanes and “The Frogs.” As I read a joke sprang to my mind, could say it just hopped right into my head. What happened to the poet who wrote about the prose of James of Joyce and Frogs? She Croaked. All joking aside at the top of the second page of Finnegans Wake, page four in my edition, “What clashes here of wills gen wonts, oystrygods gaggin fishygods! Brékkek Kékkek Kékkek! Kóax Kóax Kóax! Ualu Ualu Ualu! Quáouauh!” Here the reader is confronted with Aristophanes’ amphibian war chant in a drunken revelry of Dionysian language. What can we glean from this?

The clash described, if taken literally, situates the divine evolutionary relationship between the oyster and the fish, “oystrygods gaggin fishygods.” The hard exoskeleton of the oyster protects its soft primitive boneless flesh that gags the fish trying to devour it. Nevertheless the complex digestive system and framework that builds and nourishes the fish’s endoskeleton ensures that in this battle, the fish will crack open this shell, and feast upon what is found inside. This is a brain and muscles at work. This is the eternal cycle of conflict in evolution and adaptation that Joyce frames as Shem and Shaun, a collectively conscious variation on Cain and Able.

Consulting the notes reveals a deeper understanding than the literal representations of the words themselves. “Oystrygods” and “fishygods” become Ostrogoths and Visigoths and the clash becomes Catalounian Fields. The “gen” of “wills gen wonts” becomes the German word “gegen” or against. The conflict has grown to encompass Roman-Goth and from this Catholic-Protestant, Irish-European, etc. I would argue Shem and Shaun are also present with Shem playing the part of Aetius and Shaun that of Attila.

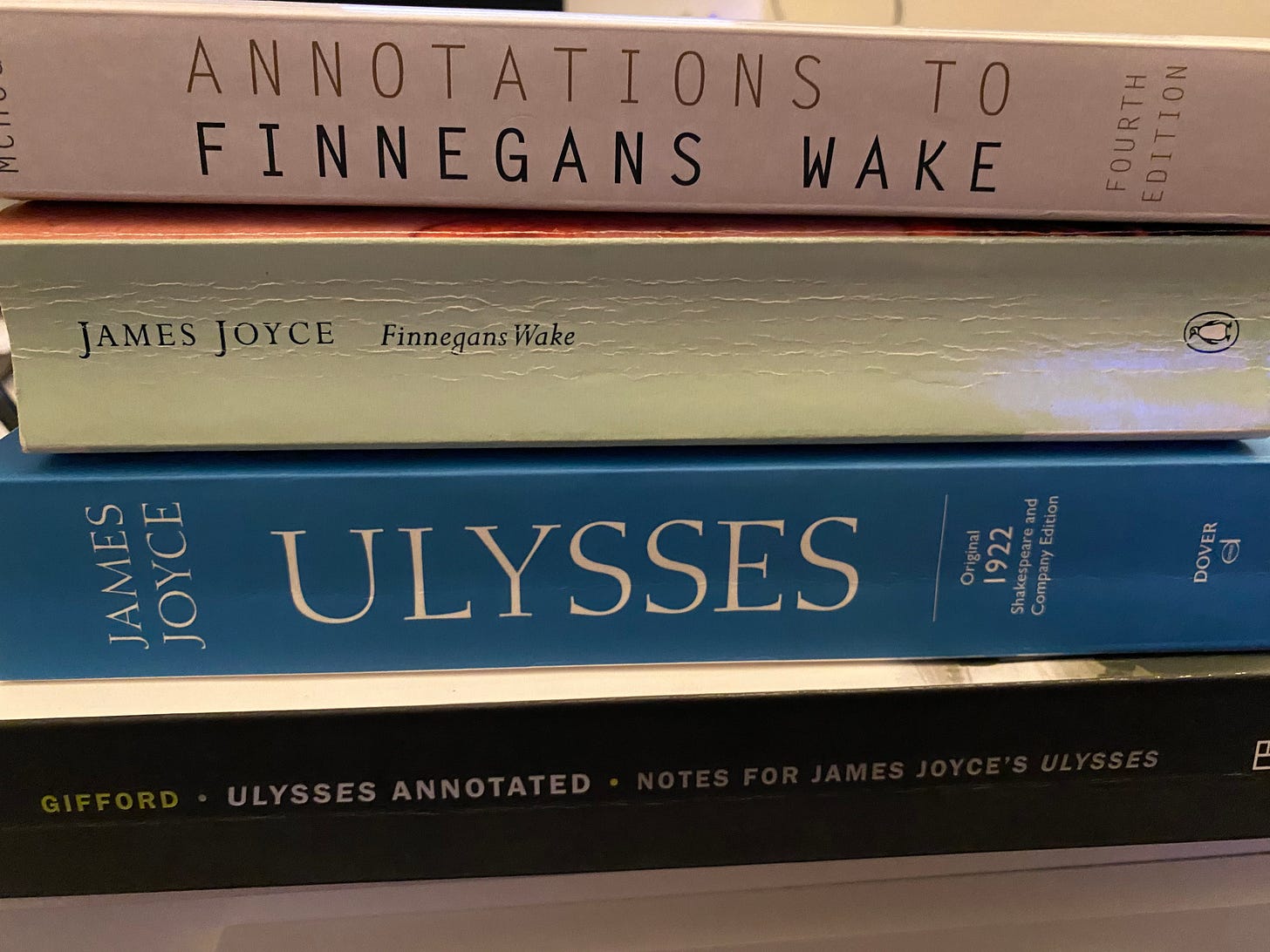

The Wake would frame the headache the readers get from this way of thinking as “Malachus Micgranes” in reference to the character Malachi Mulligan and a typical Joycean pun with the word migraines. I would argue the feast derived from this eternal conflict is none other than the Eucharist mass said by Buck Mulligan at the beginning of the novel Ulysses. This is Joyce’s way of saying this is how words are made flesh, and if this is true, then flesh must become words.

The opening chapter of Ulysses is where harsh reality meets the divine perfection of the message. Here perfection means that nothing will be changed, because nothing can be changed, and this only qualifies as “moral good” as apart of some greater determinism. Mulligan is Claudius to Stephen’s Hamlet after all, and his shaving Mass is a “mockery.” Stephen will not be locked in this tower much longer once he lets his hair down and learns to write with Molly’s voice. This frames Mulligans back handed compliment of suggesting Haines get, “Five lines of text and ten pages of notes about the folk and the fishgods of Dundrum.” This recalls Jesus feeding the five thousand with loaves and fish, as well as the selection from The Wake.

How does any of this get us to Aristophanes and “The Frogs?” The chant booms and falls like artillery shells with words like “camibalistics” being used to describe it. If Shem and Shaun are Aetius and Attila, then it follows they are also Wellington and Napoleon respectively. This can be taken for granted with the Wakes’ “museyroom” passages with “Wilingdon” and “Lipoleum” but it seems “wills gen wonts” introduces this theme. The frogs’ chant takes on a French signifigance that carries the weight and anguish of a battlefield. From the crater that formed from the giant’s fall off the ladder into a pond, and so the frogs’ sing into the long night and finds new life again when blessed by the god of wine. This is our communion.

On a completely unrelated note I was listening to an audio performance of Ulysses with Jessica, my wife. We made it through Night Town in about four sittings. While appreciating the distinct formalism my lovely wife told me that “Frog Fractions” was the Ulysses of video games. I couldn’t have said it better myself. For any literaries who don’t play video games, now you know how it feels.

Special thanks to Armand D’Angour for inspiring this essay.

Glad to have got you thinking about Frogs!